We got a few days off on half term, before the group rehearsals started, and that is when I began the process of analysing and understanding the character, creating the internal monologue which I kept in my mind every time I was saying my lines. When I was at home, I rehearsed the role saying the lines out loud in my room, to get used to the role and to learn them. I managed to keep the text and subtext in my mind when the official group rehearsals started. The rehearsals went really well, it took us some time to get used to the Shakespearian language and to know our lines by heart, but we helped each other every time and we never forgot to say the key line so we didn't confuse the others. We worked together as an ensemble, we had a lot of fun with our characters in rehearsals, we helped each other to understand the storyline of the play and the story behind the text, also our teachers helped us with understanding where is our place throughout the play, who we are and what is our purpose in there. They also helped us with building the right energy, they listened to our ideas and proposals when they were directing and also added some of our ideas which built our confidence and helped us enjoy the piece of theatre. Even if it seemed to be old and boring at the beginning, we made it fun and interesting until the end. I am so happy that I've been a part of this project, I learnt how to love every single role that I receive even if I'm not content with it at first sight. I learnt that it doesn't matter what role you have because if you work hard and put emotion into it, you won't only show the audience but to yourself,as well , the best version of your representation of the character.

As part of the advertising area, we have decided to invite families and friends, some of us even posting about it on social media, which increased the chances of more people attending the performance. The college had also invited a theatre company to see us, in order for us to get that real emotion of being on stage in front of strangers and not only family members or friends. We had two performances, of which one in the afternoon, where all the performing arts classes attended, and one in the evening, where our guests and the theatre company were invited. The college had also provided for the guests programmes of the play, handed to each individual when entering the venue.

Research:

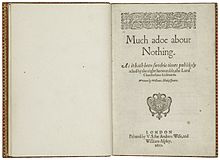

Much Ado About Nothing is a comedy by William Shakespeare thought to have been written in 1598 and 1599, as Shakespeare was approaching the middle of his career. The play was included in the First Folio, published in 1623. Much Ado About Nothing is generally considered one of Shakespeare's best comedies because it combines elements of mistaken identities, love, robust hilarity with more serious meditations on honour, shame, and court politics.

By means of "noting" (which, in Shakespeare's day, sounded similar to "nothing" as in the play's title,[1][2] and which means gossip, rumour, and overhearing), Benedick and Beatrice are tricked into confessing their love for each other, and Claudio is tricked into rejecting Hero at the altar on the erroneous belief that she has been unfaithful. At the end, Benedick and Beatrice join forces to set things right, and the others join in a dance celebrating the marriages of the two couples.

Summary[edit]

At Messina, a messenger brings news that Don Pedro, a prince from Aragon, will return that night from a successful battle, Claudio being among his soldiers. Beatrice, Leonato's niece, asks the messenger about Benedick and makes sarcastic remarks about his ineptitude as a soldier. Leonato explains that "There is a kind of merry war betwixt Signior Benedick and her."[3]

Upon the arrival of the soldiers, Leonato welcomes Don Pedro and invites him to stay for a month, Benedick and Beatrice resume their "merry war," and Pedro's illegitimate brother Don John is introduced. Claudio's feelings for Hero, Leonato's only daughter, are rekindled upon seeing her, and Claudio soon announces to Benedick his intention to court her. Benedick, who openly despises marriage, tries to dissuade his friend but Don Pedro encourages the marriage. Benedick swears that he will never get married. Don Pedro laughs at him and tells him that when he has found the right person he shall get married.

A masquerade ball is planned in celebration of the end of the war, giving a disguised Don Pedro the opportunity to woo Hero on Claudio's behalf. Don John uses this situation to get revenge on his brother Don Pedro by telling young Claudio that Don Pedro is wooing Hero for himself. A furious Claudio confronts Don Pedro, but the misunderstanding is quickly resolved and Claudio wins Hero's hand in marriage.

Meanwhile, Benedick disguises himself and dances with Beatrice. Beatrice proceeds to tell this "mystery man" that Benedick is "the prince's jester, a very dull fool." Benedick, enraged by her words, swears he will have revenge. Don Pedro and his men, bored at the prospect of waiting a week for the wedding, harbour a plan to match-make between Benedick and Beatrice. They arrange for Benedick to overhear a conversation in which they declare that Beatrice is madly in love with him but afraid to tell him; that their pride is the main impediment to their courtship. Meanwhile, Hero and her maid Ursula ensure Beatrice overhears them discuss Benedick's undying love for her. The tricks have the desired effect: both Benedick and Beatrice are delighted to think they are the object of unrequited love, and both accordingly resolve to mend their faults and reconcile.

Meanwhile, Don Pedro's brother Don John, the "bastard prince", plots to prevent the wedding, embarrass his brother and wreak misery on Leonato and Claudio. He informs Don Pedro and Claudio that Hero is unfaithful, and arranges for them to see John's associate Borachio enter her bedchamber where he has an amorous liaison (actually with Margaret, Hero's chambermaid). Claudio and Don Pedro are taken in, and Claudio vows to humiliate Hero publicly.

At the wedding the next day, Claudio denounces Hero before the stunned guests and storms off with Don Pedro. Hero faints. Her humiliated father Leonato expresses the wish that she would die. The presiding friar intervenes, believing Hero to be innocent. He suggests the family fake Hero's death in order to extract the truth and Claudio's remorse. Prompted by the day's harrowing events, Benedick and Beatrice confess their love for each other. Beatrice then asks Benedick to slay Claudio as proof of his devotion, since he has slandered her kinswoman. Benedick is horrified and at first, denies her request. Leonato and his brother Antonio blame Claudio for Hero's apparent death and challenge him to a duel. Benedick then does the same.

Luckily, on the night of Don John's treachery, the local Watch apprehended Borachio and his ally Conrade. Despite the comic ineptness of the Watch (headed by constable Dogberry, a master of malapropisms), they have overheard the duo discussing their evil plans. The Watch arrest the villains and eventually obtain a confession, informing Leonato of Hero's innocence. Though Don John has fled the city, a force is sent to capture him. Claudio, stricken with remorse at Hero's supposed death, agrees to her father's demand that he marry Antonio's daughter, "almost the copy of my child that's dead"[3] and carry on the family name.

At the wedding, the bride is revealed to be Hero, still living. Claudio is overjoyed. Beatrice and Benedick, prompted by their friends' interference, finally and publicly confess their love for each other. As the play draws to a close, a messenger arrives with news of Don John's capture – but Benedick proposes to postpone his punishment to another day so that the couples can enjoy their new-found happiness. Don Pedro is lonely because he hasn't found love. Thus Benedick gives him the advice "Get thee a wife."

Sources[edit]

Stories of lovers deceived into believing each other false were common currency in northern Italy in the sixteenth century. Shakespeare's immediate source could have been one of the Novelle ("Tales") by Matteo Bandello of Mantua, dealing with the tribulations of Sir Timbreo and his betrothed Fenicia Lionata in Messina after King Piero's defeat of Charles of Anjou, perhaps through the translation into French by François de Belleforest.[4] Another version featuring lovers Ariodante and Ginevra, with the servant Dalinda impersonating Ginevra on the balcony, appears in Book V of Orlando Furioso by Ludovico Ariosto, published in an English translation in 1591.[5] The character of Benedick too has a counterpart in a commentary upon marriage in Orlando Furioso,[6] but the witty wooing of Beatrice and Benedick is original and very unusual in style and syncopation.[4] One version of the Claudio/Hero plot is told by Edmund Spenser in "The Faerie Queen" (Book II, Canto iv).[7]

Date and text[edit]

The earliest printed text states that Much Ado About Nothing was "sundry times publicly acted" prior to 1600 and it is likely that the play made its debut in the autumn or winter of 1598–1599.[8] The earliest recorded performances are two that were given at Court in the winter of 1612–1613, during the festivities preceding the marriage of Princess Elizabeth with Frederick V, Elector Palatine (14 February 1613). The play was published in quarto in 1600 by the stationers Andrew Wise and William Aspley. This was the only edition prior to the First Folio in 1623.

Analysis and criticism[edit]

Style[edit]

The play is one of the few in the Shakespeare canon where the majority of the text is written in prose.[9] The substantial verse sections are used to achieve both courteous decorum, on the one hand, and impulsive energies, on the other.[10]

Setting[edit]

Much Ado About Nothing is set in Messina, a port on the island of Sicily, which is next to the toe of Italy. Sicily was ruled by Aragon at the time the play was set.[11] The action of the play takes place mainly at the home and on the grounds of Leonato's Estate.

Themes and motifs[edit]

Gender roles[edit]

Benedick and Beatrice quickly became the main interest of the play, to the point where they are today considered the leading roles, even though their relationship is given equal or lesser weight in the script than Claudio and Hero's situation. Charles II even wrote 'Benedick and Beatrice' beside the title of the play in his copy of the Second Folio.[12] The provocative treatment of gender is central to the play and should be considered in its Renaissance context. While this was reflected and emphasised in certain plays of the period, it was also challenged.[13] Amussen[14] notes that the destabilising of traditional gender clichés appears to have inflamed anxieties about the erosion of social order. It seems that comic drama could be a means of calming such anxieties. Ironically, we can see through the play's popularity that this only increased people's interest in such behaviour. Benedick wittily gives voice to male anxieties about women's "sharp tongues and proneness to sexual lightness".[13] In the patriarchal society of the play, the men's loyalties were governed by conventional codes of honour and camaraderie and a sense of superiority to women.[13] Assumptions that women are by nature prone to inconstancy are shown in the repeated jokes on cuckoldry and partly explain Claudio's readiness to believe the slur against Hero. This stereotype is turned on its head in Balthasar's song, which shows men to be the deceitful and inconstant sex that women must suffer.

Infidelity[edit]

A theme in Shakespeare is cuckoldry or the infidelity of a wife. Several of the characters seem to be obsessed by the idea that a man has no way to know if his wife is faithful and therefore women can take full advantage of that fact. Don John plays upon Claudio's pride and fear of cuckoldry, which leads to the disastrous first wedding. Many of the males easily believe that Hero is impure and even her father readily condemns her with very little proof. This motif runs through the play, often in references to horns, a symbol of cuckoldry.

In contrast, Balthasar's song "Sigh No More" tells women to accept men's infidelity and continue to live joyfully. Some interpretations say that Balthasar sings poorly, undercutting the message. This is supported by Benedick's cynical comments about the song, where he compares it to a howling dog. However, in the 1993 Branagh film Balthasar sings beautifully, the song is also given a prominent role in both the opening and finale and the message appears to be embraced by the women in the film.[15]

Deception[edit]

In Much Ado About Nothing, there are many examples of deception and self-deception. The games and tricks played on people often have the best intentions—to make people fall in love, to help someone get what they want, or to make someone realise their mistake. However, not all are meant well, such as when Don John convinces Claudio that Don Pedro wants Hero for himself, or when Borachio meets 'Hero' (who is actually Margaret, pretending to be Hero) in Hero's bedroom window.

Masks and mistaken identity[edit]

People are constantly pretending to be others or being mistaken for other people. An example of this is Margaret who is mistaken for Hero, which leads to Hero's public disgrace at her wedding with Claudio. However, during a masked ball in which everyone must wear a mask, Beatrice rants about Benedick to a masked man who turns out to be Benedick himself but Beatrice is unaware of this at the time. During the same celebration, Don Pedro, masked, pretends to be Claudio and courts Hero for him. After Hero is announced "dead," Leonato orders Claudio to marry his "niece," who is actually Hero in disguise.

Noting[edit]

Another motif is the play on the words nothing and noting, which in Shakespeare's day were near-homophones.[16] Taken literally, the title implies that a great fuss ("much ado") is made of something which is insignificant ("nothing"), such as the unfounded claims of Hero's infidelity and the unfounded claims that Benedick and Beatrice are in love with one another. The title could also be understood as Much Ado About Noting. Much of the action is in interest in and critique of others, written messages, spying, and eavesdropping. This is mentioned several times, particularly concerning "seeming," "fashion," and outward impressions. Nothing is a double entendre; "an O-thing" (or "n othing" or "no thing") was Elizabethan slang for "vagina", evidently derived from the pun of a woman having "nothing" between her legs.[4][17][18]

Examples of noting as noticing occur in the following instances: (1.1.131–132)

and (4.1.154–157).

At (3.3.102–104), Borachio indicates that a man's clothing doesn't indicate his character:

A triple play on words in which noting signifies noticing, musical notes and nothing occurs at (2.3.47–52):

Don Pedro's last line can be understood to mean, "Pay attention to your music and nothing else!" The complex layers of meaning include a pun on "crotchets," which can mean both "quarter notes" (in music) and whimsical notions.

The following are puns on notes as messages: (2.1.174–176),

in which Benedick plays on the word post as a pole and as mail delivery in a joke reminiscent of Shakespeare's earlier advice "Don't shoot the messenger"; and (2.3.138–142)

in which Leonato makes a sexual innuendo concerning sheet as a sheet of paper (on which Beatrice's love note to Benedick is to have been written) and a bedsheet.

(Wikipedia, 2017, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Much_Ado_About_Nothing)

Character Analysis Beatrice

Beatrice is one of the most delightful characters in all of Shakespeare — certainly one of the most talkative and witty. She is likely to touch a responsive chord with many readers and playgoers today in light of current social ideas that encourage greater equality and self-assertiveness for women than has been traditional for women of the Western world. The traditional woman of the Elizabethan period, especially of Beatrice's class, is better represented by her cousin Hero — the naive, chaste, and quiet young woman of whom Beatrice is extremely protective. Beatrice is as cunning and forward as Hero is naive and shy.

Beatrice often interrupts or speaks her mind without concern about decorum. Her first line interrupts the conversation between Leonato and the messenger and is loaded with sarcasm and bitterness. Throughout the play, she is very clever with words, displaying considerable intellectual faculty as well as a natural ability for humor. And her way with words is sharpened when the object of her humor is Benedick.

Beatrice's unexplained bitterness toward Benedick is displayed right from the beginning. Then we begin to realize she has been hurt by him. Still stinging from past experiences with him, now she greets him with scorn, wariness, and anger. Eventually we recognize that desire and affection for him are still buried within her. She has learned to use humor and insults to disguise deeper emotions. Yet, when she overhears Hero describing her faults, she is surprised at how she is perceived by others: "Stand I condemned for pride and scorn so much?" She vows to abandon her habits of contempt and pride, and also to let herself love Benedick openly.

Before Beatrice can express her true feelings to Benedick, she may find it so difficult to change her habits of scorn and insult that she has physical symptoms of discomfort: "I am exceeding ill. . . . I am stuffed. . . . I cannot smell." Finally in a moment of high emotion during which she rages over the deception against Hero, she is also able to tell Benedick that she loves him — first tentatively, then without constraint: "I love you with so much of my heart that none is left to protest." Yet at the end, she must have her last hesitation — joking or not:

Benedick: Do not you love me?

Beatrice: Why no, no more than reason.

Beatrice: Why no, no more than reason.

And when she finally agrees to marry him, she has her last little gibe on the subject:

Beatrice: I would not deny you. But . . . I yield upon great persuasion, and partly to save your life, for I was told you were in a consumption.

Has Beatrice changed over the week or so of the play's time-line? At the very least, her tongue is not so sharp and belittling; at best, she has let herself love and be loved — a miraculous change in such a strong, independent woman.

(CliffsNotes, 2016, https://www.cliffsnotes.com/literature/m/much-ado-about-nothing/character-analysis/beatrice)

My targets for the third term were to know my lines after the half term week off and to manage to get into the "character's shoes" before the performance in order to complete my full process of thoughts and actions in Beatrice's role. Also, the performance was recorded and the teachers sent us the YouTube link of the play so we can review our own work. I'm happy to say that I achieved my targets.

No comments:

Post a Comment