When I first started this course I only knew that I wanted to be a famous actress. Throughout the past two years spent in this college I learnt that being successful it is not the same thing as being famous. I learnt that acting is more than just talent, it is hard working, dedication, culture and technique. Every single unit we worked on taught me something, the ones we did this year taught me how to write a script, how to listen to everyone's opinions, how to build a character, how to use my imagination properly when needed. I developed my creative skills, my acting skills and I started to learn my lines faster than I ever imagine I could. I have chosen to be a part of this industry because I feel like planting emotions into other people through your performance can be the most beautiful job someone can ever wish for. Changing people's moods and lives through a movie or a play it is almost like a doctor healing its patient. I feel like a hero when I am acting.

The concept of the project is to perform a piece of theatre of more than one hour, with professional props, sounding and lighting, so we can have the experience of professional actors. I am aiming to make the audience feel like they are watching a real piece of theatre and to learn more about acting through this experience. The beginning of this project starts with my research on the play we were given, "The Government Inspector". I am going to read the play, watch more performances of it online and read about the life experience of the people that were living back in the 19th century so I can have a better understanding of the character. I will need a costume that would fit me and my role, different props that I will decide during the rehearsals, a good team to work with and some time to get used to my character's personality. After I finish my research I will start to learn my lines and after that I will make my full thought process and start to rehearse with my colleagues so that we can become familiar with our new roles. We have enough time for everything but I will make a timescale anyway that will be shown up on my blog.

I was really happy to do this role since I felt like I could relate to Maria's character, it reminded me of my childhood. I tried to remember myself all of the moments when my only purpose in life was to get married, I acted like I was living in the past. That's how I put myself into the character. I used Stanislavski's technique mainly to have a better understanding of my role and my place into the family and Berkoff's technique to express myself better to the audience.

thoughts on your approach to the role

I was really happy to do this role since I felt like I could relate to Maria's character, it reminded me of my childhood. I tried to remember myself all of the moments when my only purpose in life was to get married, I acted like I was living in the past. That's how I put myself into the character. I used Stanislavski's technique mainly to have a better understanding of my role and my place into the family and Berkoff's technique to express myself better to the audience.

thoughts on your approach to the role

Evaluation:

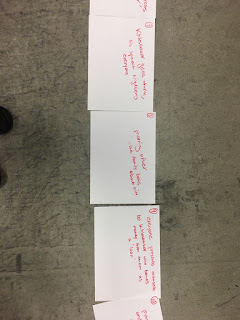

Now that we finished the final project I can say that everything worked as we wanted. We started off with reading the play together in class, after we finished, we had one week to decide which of the characters would suit us better, the final decision was taken by our teachers, I received Maria's role, which I actually wanted to do because I felt like I can relate to her character, also because my favourite stories always contain that spoiled and silly character that you got to love, for the first performance and the role of the third merchant for the second performance, which was a really fun and easy role to do because he did not have many lines and his purpose in the play was easy to understand, giving me the opportunity to catch some laugh from the audience. The whole play was about a poor man that was mistaken for a governor inspector and took advantage of the stupidity of the town's folk which was trying to impress him everyday and to convince him that the governor was not right for their town. The whole play revolves around the differences between the different social classes that were having distinct familiar values correlated to their fortunes. The satire highlights the wrong actions of the country people that were disappointed in the system that they had to live in, saying that it was corrupted, at the same time bribing the government inspector to change this, which is ironic because you can only change the society if you are the change that you want to see in the world and they clearly didn't know that. They took the "bad" governor as their role model and they acted just like him, which is normal in a small town because people tend to adapt to their behaviour the habits they see in powerful people, the governor being the most powerful person they have ever seen in their life. In order to learn more about every single social class we had to do some exercises which involved all of us. One of the exercises was to walk around the room with different attitudes, sometimes poor, some other times rich or even superior and inferior. Later, we had to do the same exercise with the attitude of our character depending on the social rank. We had another exercise where everyone had to write on coloured papers, on the orange ones we had to describe a character, on the white ones we had to write down a piece of the story and on the red ones a theme from the play. It was a beautiful exercise, we worked together as a team and we started to understand even better the meaning of the play and our characters. Also, after we finished writing down everything we had to choose one paper out of every single category and to act out what we picked. Then, we had to organise the characters by the social rank and the stories by the chronological order. I can say that it was really fun and engaging to work on this project and that I enjoyed every single moment of rehearsals with my group. This time we got together very well, I can say that we didn't have any problems coming up during the process of rehearsals. When the day of the performance came we were all ready to do the best show we did so far and that is what happened there. We received a good feedback from our teachers, they said our show was above expectations. Furthermore, the audience laugh at our jokes, they enjoyed the show and in the end we received an even better feedback from them, they said our show was next level and that they enjoyed our show just like they enjoy a high end theatre play. I am content about my achievements so far and I can only say that I am going to miss everyone in this college and that I am grateful for all of the things I learnt during my time here.

Research:

Cover of the first edition

The Government Inspector, also known as The Inspector General (Russian: «Ревизор», Revizor, literally: "Inspector"), is a satirical play by the Russian and Ukrainian dramatist and novelist Nikolai Gogol.[1] Originally published in 1836, the play was revised for an 1842 edition. Based upon an anecdote allegedly recounted to Gogol by Pushkin,[2] the play is a comedy of errors, satirizing human greed, stupidity, and the extensive political corruptionof Imperial Russia.

According to D. S. Mirsky, the play "is not only supreme in character and dialogue – it is one of the few Russian plays constructed with unerring art from beginning to end. The great originality of its plan consisted in the absence of all love interest and of sympathetic characters. The latter feature was deeply resented by Gogol's enemies, and as a satire the play gained immensely from it. There is not a wrong word or intonation from beginning to end, and the comic tension is of a quality that even Gogol did not always have at his beck and call."[3]

The dream-like scenes of the play, often mirroring each other, whirl in the endless vertigo of self-deception around the main character, Khlestakov, who personifies irresponsibility, light-mindedness, absence of measure. "He is full of meaningless movement and meaningless fermentation incarnate, on a foundation of placidly ambitious inferiority" (D. S. Mirsky). The publication of the play led to a great outcry in the reactionary press. It took the personal intervention of Tsar Nicholas I to have the play staged, with Mikhail Shchepkin taking the role of the Mayor.

source: Wikipedia

Society in the 19th Century

During the 19th century life in Britain was transformed by the Industrial Revolution. At first it caused many problems but in the late 19th century life became more comfortable for ordinary people. Meanwhile Britain became the world's first urban society. By 1851 more than half the population lived in towns. The population of Britain boomed during the 1800s. In 1801 it was about 9 million. By 1901 it had risen to about 41 million. This was despite the fact that many people emigrated to North America and Australia to escape poverty. About 15 million people left Britain between 1815 and 1914. However many people migrated to Britain in the 19th century. In the 1840s many people came from Ireland, fleeing a terrible potato famine. In the 1880s the Tsar began persecuting Russian Jews. Some fled to Britain and settled in the East End of London.

In the early 19th century Britain was ruled by an elite. Only a small minority of men were allowed to vote. The situation began to change in 1832 when the vote was given to more men. Constituencies were also redrawn and many industrial towns were represented for the first time. The franchise was extended again in 1867 and 1884. In 1872 the secret ballot was introduced. Once most men could vote movements began to get women the right to vote as well. In 1897 in Britain local groups of women who demanded the vote joined to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS).

In 19th century Britain at least 80% of the population was working class. In order to be considered middle class you had to have at least one servant. Most servants were female. Throughout the 19th century 'service' was a major employer of women.

In the 19th century families were much larger than today. That was partly because infant mortality was high. People had many children and accepted that not all of them would survive.

In the early 19th century a group of Evangelical Christians called the Clapham Sect were active in politics. They campaigned for an end to slavery and cruel sports. They gained their name because so many of them lived in Clapham. Organised religion was much more important in the 19th century than it is today. Nevertheless in 1851 a survey showed that only about 40% of the population were at church or chapel on a given Sunday. Even allowing for those who were ill or could not make it for some other reason it meant that half the population did not go to church. Certainly many of the poor had little or no contact with the church. In 1881 a similar survey showed only about 1/3 of the population of England at church on a given Sunday. In the late 19th century organized religion was in decline in Britain.

Work in the 19th Century

During the 1800s the factory system gradually replaced the system of people working in their own homes or in small workshops. In England the textile industry was the first to be transformed. The Industrial Revolution also created a huge demand for female and child labor. Children had always done some work but at least before the 19th century they worked in their own homes with their parents or on land nearby. Children's work was largely seasonal so they usually did have some time to play. When children worked in textile factories they often worked for more than 12 hours a day. In the early 19th century parliament passed laws to restrict child labor. However they all proved to be unenforceable. The first effective law was passed in 1833. It was effective because for the first time factory inspectors were appointed to make sure the law was being obeyed. The new law banned children under 9 from working in textile factories. It said that children aged 9 to 13 must not work for more than 12 hours a day or 48 hours a week. Children aged 13 to 18 must not work for more than 69 hours a week. Furthermore nobody under 18 was allowed to work at night (from 8.30 pm to 5.30 am). Children aged 9 to 13 were to be given 2 hours education a day.

Conditions in coalmines were often terrible. Children as young as 5 worked underground. However in 1842 a law banned women and boys under 10 from working underground. In 1844 a law banned all children under 8 from working. Then in 1847 a Factory Act said that women and children could only work 10 hours a day in textile factories. In 1867 the law was extended to all factories. (A factory was defined as a place where more than 50 people were employed in a manufacturing process). In 1878 a law banned women from working more than 56 hours a week in any factory. In the 19th century boys were made to climb up chimneys to clean them. This barbaric practice was ended by law in 1875.

In the 1850s and 1860s skilled craftsmen formed national trade unions. However unskilled workers did not become organised until the late 1880s.

British Cities in the 19th Century

Living conditions in early 19th British century cities were often dreadful. However there was one improvement. Gaslight was first used in 1807 in Pall Mall in London. Many cities introduced gas street light in the 1820s. However early 19th century cities were dirty, unsanitary and overcrowded. In them streets were very often unpaved and they were not cleaned. Rubbish was not collected and it was allowed to accumulate in piles in the streets. Since most of it was organic when it turned black and sticky it was used as fertilizer.

Furthermore in the early 19th century poor people often had cesspits, which were not emptied very often. Later in the century many people used earth closets. (A pail with a box containing granulated over it. When you pulled a lever clay covered the contents of the pail). In the early 19th century only wealthy people had flushing lavatories. However in the late 19th century they became common. In the early 19th century poor families often had to share toilets and on Sunday mornings queues formed.

Given these horrid conditions it is not surprising that disease was common. Life expectancy in cities was low (significantly lower than in the countryside) and infant mortality was very high. British cities suffered outbreaks of cholera in 1831-32 and in 1848-49. Fortunately the last outbreak finally spurred people into action. In the late 19th century most cities dug sewers and created piped water supplies, which made society much healthier. Meanwhile in 1842 Joseph Whitworth invented the mechanical street sweeper.

Poverty in the 19th Century

At the end of the 19th century more than 25% of the population of Britain was living at or below subsistence level. Surveys indicated that around 10% were very poor and could not afford even basic necessities such as enough nourishing food. Between 15% and 20% had just enough money to live on (provided they did not lose their job or have to take time off work through illness). If you had no income at all you had to enter the workhouse. The workhouses were feared and hated by the poor. They were meant to be as unpleasant as possible to deter poor people from asking the state for help. However during the late 19th century workhouses gradually became more humane.

Homes in the 19th Century

Well off people lived in very comfortable houses in the 19th century. (Although their servants lived in cramped quarters, often in the attic). For the first time furniture was mass-produced. That meant it was cheaper but unfortunately standards of design fell. To us middle class 19th century homes would seem overcrowded with furniture, ornaments and nick-knacks. However only a small minority could afford this comfortable lifestyle.

In the early 19th century housing for the poor was often dreadful. Often they lived in 'back-to-backs'. These were houses of three (or sometimes only two) rooms, one of top of the other. The houses were literally back-to-back. The back of one house joined onto the back of another and they only had windows on one side. The bottom room was used as a living room cum kitchen. The two rooms upstairs were used as bedrooms. The worst homes were cellar dwellings. These were one-room cellars. They were damp and poorly ventilated. The poorest people slept on piles of straw because they could not afford beds. However housing conditions gradually improved. In the 1840s local councils passed by-laws banning cellar dwellings. They also banned any new back to backs. The old ones were gradually demolished and replaced over the following decades.

In the early 19th century skilled workers usually lived in 'through houses' i.e. ones that were not joined to the backs of other houses. Usually they had two rooms downstairs and two upstairs. The downstairs front room was kept for best. The family kept their best furniture and ornaments in this room. They spent most of the their time in the downstairs back room, which served as a kitchen and living room. As the 19th century passed more and more working class people could afford this lifestyle. In the late 19th century workers houses greatly improved. After 1875 most towns passed building regulations which stated that e.g. new houses must be a certain distance apart, rooms must be of a certain size and have windows of a certain size.

By the 1880s most working class people lived in houses with two rooms downstairs and two or even three bedrooms. Most had a small garden. At the end of the 19th century some houses for skilled workers were built with the latest luxury - an indoor toilet. However even at the end of the 19th century there were still many families living in one room. Old houses were sometimes divided up into separate dwellings. Sometimes if windows were broken slum landlords could not or would not replace them. So they were 'repaired' with paper. Or rags were stuffed into holes in the glass.

In the late 19th century most homes also had a scullery. In it was a 'copper', a metal container for washing clothes. The copper was filled with water and soap powder was added. To wash the clothes they were turned with a wooden tool called a dolly. Or you used a metal plunger with holes in it to push clothes up and down. Wet clothes were wrung through a device called a wringer of mangle to dry them. The clothes wringer or mangle was invented by Robert Tasker in 1850. In 1875 a man named John B. Porter invented a portable ironing board. Sarah Boone patented an improved device in 1892. At the beginning of the 19th century people cooked over an open fire. This was very wasteful as most of the heat went up the chimney. In the 1820s an iron cooker called a range was introduced. It was a much more efficient way of cooking because most of the heat was contained within. By the mid-19th century ranges were common. Most of them had a boiler behind the coal fire where water was heated.

Gaslight first became common in well off people's homes in the 1840s. By the late 1870s most working class homes had gaslight, at least downstairs. Bedrooms might have oil lamps. Gas fires first became common in the 1880s. Gas cookers first became common in the 1890s. In the last 2 decades of the 19th century many British towns and cities installed electric street lights. However electric light was expensive and it took a long time to replace gas in people's homes.

In the early 19th century only rich people had bathrooms. People did take baths but only a few people had actual rooms for washing. In the 1870s and 1880s many middle class people had bathrooms built. The water was heated by gas. Working class people had a tin bath and washed in front of the kitchen range.

Food in the 19th Century

In the early 19th century most of the working class lived on plain food bread, butter, potatoes and bacon. Butcher's meat was a luxury. However food greatly improved in the late 19th century. Railways and steamships made it possible to import cheap grain from North America so bread became cheaper. Refrigeration made it possible to import cheap meat from Argentina and Australia. Consumption of sugar also increased. By the end of the 19th century most people were eating better food. Furthermore in the late 19th century canned food first became widely available. The rotary can opener was invented in 1870 by William Lyman. Furthermore in the 1870s margarine, a cheap substitute for butter, was invented. A man named Gail Borden patented condensed milk in 1856. John Meyenberg patented evaporated milk in 1884.

Meanwhile several new biscuits were invented in the 19th century including the Garibaldi (1861), the cream cracker (1885) and the Digestive (1892). The first chocolate bar was made in 1847. Milk chocolate was invented in 1875. The first recipe for potato crisps appeared in a book by Dr William Kitchiner in 1817.

Education in the 19th Century

In the early 19th century the churches provided schools for poor children. From 1833 the government provided them with grants. There were also dame schools. They were run by women who taught a little reading, writing and arithmetic. However many dame schools were really a child minding service. In Britain the state did not take responsibility for education until 1870. Forsters Education Act laid down that schools should be provided for all children. If there were not enough places in existing schools then board schools were built. In 1880 school was made compulsory for 5 to 10 year olds. However school was not free, except for the poorest children until 1891 when fees were abolished. From 1899 children were required to go to school until they were 12. Meanwhile girls from upper class families were taught by a governess. Boys were often sent to public schools like Eton. Middle class boys went to grammar schools. Middle class girls went to private schools were they were taught 'accomplishments' such as music and sewing.

Games and leisure in the 19th Century

In the early 19th century working people had very little leisure time. However things improved by the end of the century. In 1871 the Bank Holiday Act gave workers a few paid holidays each year. Also in the 1870s some clerks and skilled workers began to have a weeks paid annual holiday. However even at the end of the 19th century most people had no paid holidays except bank holidays. In the early 19th century everyone had Sunday off. In the 1870s some skilled workers began to have Saturday afternoon off. In the 1890s most workers gained a half day holiday on Saturday and the weekend was born. By the end of the 19th century most people had more leisure time.

Meanwhile during the 19th century sports became organized. The first written rules for rugby were drawn up in 1845. The London Football Association devised the rules of football in 1863. The first international match was held between England and Scotland in 1872. In 1867 John Graham Chambers drew up a list of rules for boxing. They were called the Queensberry Rules after the Marquis of Queensberry. The Amateur Athletics Association was founded in 1880. Polo was first played in Britain in 1869. Several new sports and games were invented during the 19th century. Although a form of tennis was played since the Middle Ages lawn tennis was invented in 1873. Snooker was invented in India in 1875. Volleyball was invented in 1895. At the end of the 19th century bicycling became a popular sport. The safety bicycle was invented in 1885 and in 1892 John Boyd Dunlop invented pneumatic tyres (much more comfortable than solid rubber ones!) Bicycling clubs became common in Victorian Britain.

Ludo was originally an Indian game. It was introduced into Britain c. 1880. Reading was also popular in the 19th century. In 1841 Edgar Allan Poe published the first detective story The Murders In The Rue Morgue. The first Sherlock Holmes story A Study in Scarlet was published in 1887 by Arthur Conan Doyle. Many middle class people also enjoyed musical evenings when they gathered around a piano and sang. Middle class people were very fond of the theater. In the late 19th century there were also music halls where a variety of acts were performed. In the 19th century going to the seaside was very popular with those who could afford it. The first pleasure pier was built at Brighton in 1823 and soon they appeared at seaside resorts across Britain.

The steam driven printing press was invented in 1814 allowing newspapers to become more common. Stamp duty on newspapers was abolished in 1855, which made them cheaper. However newspapers did not become really common until the end of the 19th century. In 1896 the Daily Mail appeared. It was written in a deliberately sensational style to attract readers with little education.

One new hobby in the 19th century was photography. Henry Fox Talbot took the first photograph in 1835. However photography was more than just a pastime. In 1871 a writer said that one of the great comforts for the working class was having a photo of a family member who was working a long way off. They could be reminded what their loved one looked like. the first cheap camera was invented in 1888 by George Eastman. Afterwards photography became a popular hobby.

In the late 19th century town councils laid out public parks for recreation. The first children's playground was built in a park in Manchester in 1859.

In the 19th century the modern Christmas evolved. Before then Christmas wasn't especially important. It was one of only many festivals celebrated during the year. However the Victorians invented the Christmas card and the Christmas cracker. The Christmas tree was known in England before the 19th century but it was really made popular when the royal were shown in a magazine illustration with one. Father Christmas or Santa Claus became the figure we know today in the 19th century.

Transport and Communications in the 19th Century

Transport greatly improved during the 19th century. In the mid 19th century travel was revolutionized by railways. They made travel much faster. (They also removed the danger of highwaymen). The Stockton and Darlington railway opened in 1825. However the first major railway was from Liverpool to Manchester. It opened in 1830. In the 1840s there was a huge boom in building railways and most towns in Britain were connected. In the late 19th century many branch lines were built connecting many villages. The first underground railway in Britain was built in London in 1863. Steam locomotives pulled the carriages. The first electric underground trains began running in London in 1890. From 1829 horse drawn omnibuses began running in London. They soon followed in other towns. In the 1860s and 1870s horse drawn trams began running in many towns. Karl Benz and Gottlieb Daimler made the first cars in 1885 and 1886. The motorbike was patented in 1885. Also in the 1880s the safety bicycle was invented and cycling soon became a popular hobby.

Meanwhile at sea travel was revolutionized by the steam ship. By 1815 steamships were crossing the English Channel. Furthermore it used to take several weeks to cross the Atlantic. Then in 1838 a steamship called the Sirius made the journey in 19 days. However steam did not completely replace sail until the end of the 19th century when the steam turbine was used on ships. By the mid 19th century life boats were commonly carried on ships.

In the early 19th century the recipient of a letter had to pay the postage, not the sender. Then in 1840 Rowland Hill invented the Penny Post. From then on the sender of a letter paid. Cheap mail made it much easier for people to keep in touch with loved ones who lived a long way off. The telegraph was invented in 1837. A cable was laid across the Channel in 1850 and after 1866 it was possible to send messages across the Atlantic. A Scot, Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone in 1876. The first telephone exchange in Britain opened in 1879.

Clothes in the 19th Century

In the 19th century, apart from cotton shirts, men's clothes consisted of three parts. In the 18th century they wore knee length breeches but in the 19th century men wore trousers. They also wore waistcoats and coats. In the early 19th century women wore light dresses. In the 1830s they had puffed sleeves. In the 1850s they wore frames of whalebone or steel wire called crinolines under their skirts. In the late 1860s women began to wear a kind of half crinoline. The front of the skirt was flat but it bulged outwards at the back. This was called a bustle and it disappeared in the 1890s. From the 1840s onward it was fashionable for women to have very small waists so they wore corsets. Meanwhile about 1800 women started wearing knickers. At first they were called drawers. Originally women wore a pair of drawers i.e. they were actually two garments, one for each leg, tied together at the top. In the late 19th century in Britain women's drawers were called knickerbockers then just knickers.

Before the 19th century children were always dressed like little adults. In that century the first clothes made especially for children appeared such as sailor suits. A number of inventions to do with clothing were made in the 19th century. Thomas Hancock invented elastic in 1820. The safety pin was invented in 1849 by Walter Hunt. The electric iron was invented by Henry Seely in 1882 but it did not become common until the 1930s. The zip fastener was invented in 1893. In 1863 Butterick made the first paper dress pattern.

Health and Medicine in the 19th century

Medicine and surgery made great advances in the 19th century. Louis Pasteur 1822-1895 proved that disease was caused by microscopic organisms. He also invented a way of sterilizing liquids by heating them (called pasteurization). He also invented vaccination for anthrax (which killed many domestic animals) and for rabies. Immunization against diphtheria was invented in 1890. A vaccine for typhoid was invented in 1897.

Surgery was greatly improved by the discovery of anesthetics. James Simpson began using chloroform for operations in 1847. In 1865 Joseph Lister discovered antiseptic surgery, which enabled surgeons to perform many more complicated operations. Rubber gloves were first used in surgery in 1890. Then in 1895 x-rays were discovered. Nursing was greatly improved by two nurses, Florence Nightingale 1820-1910 and Mary Seacole 1805-1881 who both nursed soldiers during the Crimean War 1854-56.

Warfare in the 19th century

The industrial revolution transformed warfare. Railways meant armies could be transported much faster than before. The telegraph meant that messages could also be transmitted much faster. At the beginning of the 19th century Sir William Congreve (1772-1828) developed the Congreve rocket. These rockets were used at Copenhagen in 1807 and they set most of the town on fire. However rockets lacked both range and accuracy and after the Napoleonic Wars they fell from favor. Meanwhile in 1807 a Scot named Alexander Forsyth patented the percussion cap. When a trigger was pulled a hammer hit a container of fulminate of mercury, which exploded and ignited the charge of gunpowder. The percussion cap replaced the flintlock. Furthermore breech loading guns greatly increased the rate of fire. The British army began using breech loading guns in 1865. The range of guns was improved by rifling. Some guns had been rifled for centuries but it only became commonplace in the 19th century. In the late 19th century rifles were improved further by the introduction of magazines, which greatly increased the rate of fire.

Meanwhile in 1836 Samuel Colt began making revolvers. Traditionally the cavalry fought with pistols and swords but the revolver made swords obsolete. In the 19th century many people experimented with machine guns. In 1862 Richard Gatling invented the Gatling gun. However the first really successful machine gun was the maxim gun, invented by Hiram Maxim in 1884. It was adopted by the British army in 1889.

War at sea was changed by exploding shells, by steam engines and by iron ships. In 1858 the French launched La Gloire. It was made with plates of iron fixed onto timber. However in 1860 Britain launched HMS warrior. This ship was made with an iron hull instead of a wooden hull with iron plates fixed on. Soon the traditional gun deck on warships was replaced by turret guns on the top deck. Then in the 1860s Robert Whitehead developed the modern torpedo. The British navy began making torpedoes in 1871. In the 19th century new explosives were invented to replace gunpowder. TNT was invented in 1863 and dynamite followed in 1867. Cordite was invented in 1889. Meanwhile conditions in the services greatly improved. Uniforms were introduced for sailors in 1857. Flogging in the army and navy was abolished in 1881.

RUSSIAN SOCIETY

One representation of the ‘Russian wedding cake’, showing social divisions.

Russian society at the end of the late 19th century was strongly hierarchical. Tsarist political structures, religious and social values, rules governing land ownership and Russia’s legal code all reinforced the nation’s social hierarchy, defining position and status and restricting social mobility (movement between the classes). Russia’s social structure was often depicted and lampooned in visual propaganda, such as several versions of the ‘Russian wedding cake’ (see picture, left). In these depictions, Russian society is shown as a feudal pyramid, the upper classes propped up by the labour of the working masses – who are usually kept in check with work, religion and the threat of violence. In reality the ‘cake’s’ base was broader than these images suggest. The poor peasantry and the industrial working-class made up more than four-fifths of the population; while Russia’s educated and professional middle classes were tiny when compared to societies in Britain or France.

According to historian Michael Lynch, the 1897 census categorised the population of Russia in these broad class groups:

Upper classes: Royalty, nobility, higher clergy: 12.5 per cent.

Middle classes: Merchants, bureaucrats, professionals: 1.5 per cent.

Working classes: Factory workers, artisans, soldiers, sailors: 4 per cent.

Peasants: Landed and landless farmers: 82 per cent.

Middle classes: Merchants, bureaucrats, professionals: 1.5 per cent.

Working classes: Factory workers, artisans, soldiers, sailors: 4 per cent.

Peasants: Landed and landless farmers: 82 per cent.

Nestled atop this metaphorical pyramid was Russia’s royalty and aristocracy, who for the most part lived lives of comfort, isolated from the dissatisfactions of the lower classes. Noble titles and land ownership were the main determinants of privilege in tsarist Russia. The tsar himself was a significant land owner, holding the title of as much as ten per cent of arable land in western Russia. The Russian Orthodox church and its higher clergy also owned large tracts of land. The abolition of serfdom in 1861 allowed many land-owners to increase their holdings, largely at the expense of the state and emancipated serfs. Protective of their wealth and privilege, Russia’s landed aristocracy were arguably the most conservative force in the empire. Many of the tsar’s ministerial advisors were drawn directly from their ranks and worked to block or shout down suggested reforms. Sergei Witte – himself an aristocrat, though one without large land holdings – claimed that “many of the aristocracy are unbelievably avaricious [greedy] hypocrites, scoundrels and good-for-nothings”.

“The attitude of the [tsarist] regime to the nobility depended on the circumstances of each individual reign. All tsars, however, considered the nobility to be the key class in terms of wealth and social leadership. They underpinned the social hierarchy that was an integral part of the whole concept of political autocracy. Without this, the political system would be unable to operate effectively. Some of the nobility were involved in the governing process – but this was not their key importance. As in Prussia, the tacit understanding was that the nobility’s social powers were enhanced in return for an acceptance of autocracy that did not essentially involve a contribution towards its exercise.”

Stephen J. Lee, historian

Russia’s middle-classes worked both for the state (usually in the higher ranks of the bureaucracy) or the private sector, either as small business owners or trained professionals (such as doctors, lawyers and managers). Industrial growth in the 1890s helped to expand the middle-classes by increasing the ranks of factory owners, businessmen and entrepreneurs. The middle-classes tended to be educated, worldly and receptive to liberal, democratic and reformist ideas. Members of the middle-class were prominent in political groups like the Kadets (Constitutional Democrats) and, later, in the Duma.

By far the largest social class in Russia was the peasantry. Most Russian peasants worked small plots of land using antiquated farming methods. Farming in Russia was a difficult business, dictated by the soil, the weather and sometimes pure luck. It tended to be easier in Russia’s ‘breadbasket’ southern regions, where the soil was dark and rich and the climate more temperate. Grain crops like barley, rye and oats flourished in these areas. Further north and east, across the Urals and toward Siberia, the soil was harder and less fertile, so grain production was more difficult. Peasants here relied more on tuber crops like potatoes, turnips and beets. In much of Siberia the soil was hard, frozen and unsuitable for farming. Russian farming was further hindered by its reliance on methods and techniques that were not far removed from the Middle Ages. Most peasants cleared, ploughed and sowed the land by hand, without the benefit of machinery or chemical fertilisers. A few of the more prosperous peasants had beasts of burden.

A group of Russian peasants shortly before World War I.

Before 1861 most peasants had been serfs, with no legal status or rights as free men. Alexander II’s emancipation edict gave them legal freedom – but the land redistribution that followed often thousands of peasants worse off than before. The best tracts of farmland were usually allocated to land-owning nobles, who kept it for themselves or leased it for high rents. The former serfs were left with whatever remained – but they were obliged to make 49 annual redemption payments to the government – in effect, a 49-year state mortgage. These redemption payments were often higher than the rent or land taxes they paid before emancipation. Some common land was also controlled and allocated by the obshchina or mir (or village commune). The mir was also responsible for other administrative duties, such as the collection of taxes and the supply of conscript quotas to the Imperial Army.

The small size of these peasant communes (most villages contained between 200-500 people), as well as their scattered distribution, affected the worldview of Russian peasants. There was little or no formal education so the majority of peasants were illiterate; few peasants travelled and returned, so not much was known about the world beyond their village. Peasant communities were insular and defensive: they relied on each other for information and became suspicious, even paranoid about outsiders and strangers. Few peasants had any understanding about government, politics or economics. Many were intensely religious and superstition to the point of medievalism; they believed in magic, witchcraft and devilry and carried symbols and icons to ward off bad luck. A sizeable proportion of the peasantry was loyal to the tsar; a similar number knew little of him and cared even less. They hated the bureaucracy for its taxes, regulations and impositions; they feared the army for taking away their sons; they trusted few other than their own.

But for all their political apathy, the peasantry was occasionally roused to action – particularly by changes that affected them directly, such as food shortages or new taxes. There were significant peasant protests in 1894 when the government introduced a state monopoly on vodka production (previously the peasants could distil their own, provided they paid a small excise to the state). Peasants were also receptive to anti-Semitic hatred and ready to blame Russia’s Jews for everything from harvest failures to missing children. Whipped up by rumours and agitators, Russia’s peasants carried out dozens of pogroms in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Peasant unrest and violence would later erupt during the 1905 Revolution, though it was directed at land-owners more than the government. Though peasant uprisings were never widespread or coordinated, they were nevertheless a worrying sign for the tsarist regime.

A meeting of mirskoi skhod(village elders) in a Russian peasant mir.

Regardless of class or status, Russian society was deeply patriarchal. Men were dominant in the community, the workplace and the government. This was not just a product of social values, it was codified in law. The Russian legal code gave husbands almost unlimited power to make decisions within the family. Wives were expected to concede to and obey their husbands. Married women needed their husband’s express permission to take a job, apply for most government permits, obtain a passport or commence higher education. Russian women could not initiate divorce proceedings (though a husband’s legal authority over his family could be removed in cases of incompetence, such as alcoholism or mental illness). If a man died then his male children inherited most of his property; his wife and daughters received only a small share. The average age of marriage for Russia’s peasant women was 20; for the aristocracy and middle-classes it was a few years older. Russia had one of the highest child mortality rates of the Western world. By the late 1800s, around 47 per cent of children in rural areas did not survive to their fifth birthday.